Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Desert-Forest or Wilderness

To contact us by email click the button

Hautdesert, the desert-forest of the Cistercians

For the Cistercians during the middle-ages, the biblical wilderness and desert of the bible, had become the uncultivated forests of western Europe. Jacques Le Goff notices that the role played by ‘desert’ in early monastiscism in the east was later adopted by woodland in medieval Europe, this being the ‘desert-forest’ of the Cistercians. ‘Desert’ was a Cistercian/ecclesiastical term for ‘forest’ an area under forest law, specifically the uninhabited, untamed woodland where they had first settled and built their abbeys and given the rights to the land as lord.

An area which was covered by Forest Law was known as ‘Forest’. This is not forest as we understand it, an area covered with trees, it could be grassland, moors, swamps, as well as woodland. High forest is conventional woodland, sometimes called primeval or ancient woodland, allowed to grow unmanaged by man but may be felled for timber.

Peter Szabo notices that ‘desertum’ was usually a reference to woods. – see Woodland and forests in medieval Hungary.

The Cistercians cultivated the image of themselves as ‘desert monks’, and their regulations stated that their abbeys should be located ‘far from the dwellings of men’, or, in the words of Orderic Vitalis, ‘in lonely wooded places’ – From “Who were the Cistercians?” By Professor Janet Burton. These lonely wooded places in Medieval Europe, would have been areas under forest law. Abbey lands were usually given to abbeys by Kings, Princes or Lords of private forests. These lands would be ‘forestis’ and so would be governed by forest law.

Wood – Sometimes wood signified a forest mountain range, as with the Bohmerwald in Germany. Sometimes it signified a boundary, a protective zone. But the original basic meaning of wood usually prevailed: wilderness or even desert. See Discovering the vernacular landscape – By John Brinckerhoff Jackson.

To emphasize that forest was an area where no one else had any rights, the words ‘eremus, ‘solitudo’ or ‘deserto’ were often added to the ‘forestis nostra’.

The benedictine tironensian monk Gaufridus Grossus, used the terms desert and forest interchangeably.

In the Gawain poem the poet refers to the ‘Wyldrenesse of Wyrale’.

The following is from, Grazing Ecology and Forest History By F. W. M. Vera. See also in the same book, p.103, section 4.2. The Wilderness and the Concept of ‘Forestis’

The wilderness (‘forestis’, ‘Wald’) was used for obtaining firewood and timber, for the production of peat and metals, for grazing livestock, cutting foliage for fodder, collecting honey, and the pannage of the pigs. This use was covered by the ‘ius forestis’, also known as ‘forest law’ or ‘waldrecht’, laid down in all sorts of regulations. The origin of the term ‘forestis’ is a legal one. It served to determine the rights of the king. Terms related to the concept of the ‘forestis’ also acquired a legal meaning, because they also related to the wilderness, which had been declared by the king to be his ‘forestis’. Certain types of use of the wilderness were declared to be the king’s privilege because “the wilderness was the forestis”.

The grazing of livestock and the exploitation of timber were believed to have resulted in more and more openings in the original forest so that the wilderness, the closed forest, eventually changed into a park-like wood-pasture and ultimately into grassland or heath. Vera suggests that the meaning of ‘wilderness’ was originally the closed forest. It appears that the rest of Western Europe used the same naming conventions for uncultivated forest: In the Dutch language, the terms ‘wildernisse’ and ‘Wyldnisse’ were used respectively in the Middle Ages and subsequently, for land that was not cultivated.

‘Wilderness clearing’ meant the cutting back of ancient woodland to reveal arable land for cultivation.

As we have seen, ‘wilderness’ was a term used for the King’s forestis, a wild uncultivated forest under forest law. In 1376 the Forest of Wirral was disafforested so became land suitable for cultivation, Wirral could no longer be termed a ‘Wilderness’, uncultivated forest. This information/fact, dates the Gawain poem no later than 1376. With his detailed knowledge of hunting and forest ecology it would seem that the Gawain poet was most likely a forester, a supervisor of the hunt, he was aware of the rules of the hunt within the forest. The use of wilderness by the poet in a technical sense, meaning forestis, is most likely. The use by the poet of ‘wilderness’ to describe ‘wild country’ because outlaws lived there, is less convincing.

Desert and wilderness, the forests of western Europe

For the medieval West, the “desert” meant the forest. The Cistercians made this their “Egyptian wilderness”. Here they could find the “solitary wastes” dear to contemplatives,…….From, Cistercian Abbeys: history and architecture – Jean-François Leroux-Dhuys, John Crook (Ph.D.)

“While the wilderness of the Bible, characterised by phrases like in solitudine or ex hominibus, is often specified as desertum, it should not be understood in the modern sense of the word desert. Gaufridus (Grossus), uses the terms desert and forest interchangeably, in phrases such as “in silvis concorditer cohabitaverant,” “they had lived harmoniously in the forest,” and “deserta properanter abiit” (“he went away quickly from the desert”).” – see The Forest of Medieval Romance – Saunders.

Holtwodez: A natural wild oak wood, left to mature without man’s intervention, would be called a ‘holt’, the Gawain poet’s ‘holtwodez’. Holts were also called by foresters, high forest, haut-bois, highwood, over-vert. A high forest grown for timber only was also referred to as a ‘grove’.

Desert in English is often used for ‘wild, mountain or forest land’ – ‘A Survey and Analysis of the Place-Names of Staffordshire’ by David Horovitz, LL. B.

It would appear that the ‘wilderness of Wirral’ and the desert of ‘hautdesert’ in the Gawain poem, are Cistercian/ecclesiastical terms for what we now call forest, ‘lonely wooded places’.

The Forest of Medieval Romance: Avernus, Broceliande, Arden By Corinne J. Saunders

Bernard of Clairvaux.” Bernard emphasized the quest of the individual for spiritual fulfilment, to be reached through mystical rather than intellectual means. His promotion of the idea of the Christian as miles Christi led at the same time to the Cistercians’ active involvement in the Second Crusade. The construction of the city of God in the wilderness, the larger attempt to bring all civilizations under God’s rule, and the constant striving of man to attain the New Jerusalem, lay at the heart of the Cistercian ideal. This odd mixture of active involvement in and withdrawal from the world was to be particularly influential on the narrative patterning of romance.

It was in the monasticism and eremiticism of the West that desert met forest, for the landscape of withdrawal of Western Europe was most frequently the forest. Occasionally, the wilderness might be represented by the sea, as in tales of early Celtic monks such as Brendan, Ronan and Columban.’ This was not, however, the usual landscape associated with the Biblical tradition of the desert: … these seafaring monks were far from the norm in the West, with its temperate climate and absence of vast arid wastes. Here, “desert” -meaning solitude – was quite different from what we mean by the word desert in its usual geographical sense, almost the opposite in fact; namely, the forest.

In fact Columban and Ronan settle within the forest after their sea journeys, suggesting that both settings represent forms of wilderness for the monks.

The Biblical Wilderness

To the historical reality which underlies the romance forest must be added the second and related tradition of the Biblical wilderness or desert. The definition of the forest as uncultivated landscape, rather than simply as woodland, allowed the writers of the Middle Ages to equate easily the forest of their own times and the desert of the Bible. This desert landscape carried with it specific associations of solitude and divine inspiration which were to be appropriated as part of the forest’s symbolism in the romances. Such associations fitted in well with the idea of the forest as a separate landscape governed by its own laws and defined by its wildness. The assimilation of the Biblical traditions into the literary forest landscape is clearly illustrated by the replacement of the wilderness or desert with the forest in medieval retellings of various Biblical episodes, such as the banishment of Nebuchadnezzar or the exile of John the Baptist.

The European forest, like the Biblical desert, was frequently described in terms of emptiness and aridity, as gaste or gastine. Although, as we have seen, wasteland formed a part of the forest landscape, it seems that these words are employed to indicate a landscape empty of habitation and cultivation rather than of trees.

Medieval authors quickly assimilated the idea of the desert, wasteland or wilderness into their own perspectives, and in retellings of Biblical episodes, the desert soon became forest.

Grazing Ecology and Forest History By F. W. M. Vera

The concept forestis comprised everything which lives and grows in the wilderness or the land which has not been cultivated, i.e. the land, water, wind and every animal that lives and every plant that grows there. The term ‘forestis nostra’ not only indicated that the land concerned (‘forestis’; plural, ‘forestes’), and all the wild plants and animals living there belonged to the king; it also meant that only the king had the right to make use of these. Without his express consent, others were not permitted to graze their livestock, cut down trees, collect firewood or create fields for crops (Kaspers. 1957. pp. 23-26. 39-40). To emphasize that these were areas where no one else had any rights, the words ‘eremus’. ‘solitudo’ or ‘in deserto’ were often added to the ‘forestis nostra’.

Ironically, “desert” in the non-arid regions of northern Europe comes to bear the modern meaning of “forest” as much as anything: it is a symbolic desert, void of human culture, rather than an arid region.” Desert is wilderness, the untamed, uncultivated and therefore “useless” spaces beyond the edges of “civilization.”

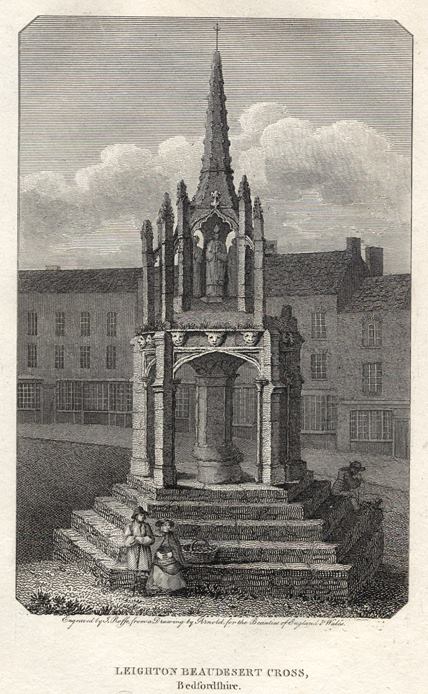

Existing uses of ‘Desert’ in place names such as Beaudesert.

It has been suggested that Hautdesert may be a reference to the Bishop’s hunting lodge, Beaudesert Hall, Longdon, Staffordshire, because the names are similar.

In the late 13th century, rights of ‘Chase’ for hunting were granted to the Bishop of Lichfield. The Bishop constructed a deerpark and hunting lodge at Beaudesert. This area was enclosed by an earthen bank and internal ditch probably topped by a wooden fence. The area outside the deerpark was mostly uninhabited, but was important to surrounding settlements for fuel, building materials, tools and for grazing sheep, cattle and pigs. Ref www.cannock-chase.co.uk

The names ‘Hautdesert’ and ‘Beaudesert’ are similar because Beaudesert was once the site of a short-lived Cistercian monastery, St. Mary’s Abbey , established in the middle of the 12th century and abandoned after less than a dozen years of tenure by the monks. The abbey at Beaudesert was within Cank forest, a royal forest under ‘forest law’. Once again the Cistercian term ‘desert’ is used to describe a chosen location within a wild uncultivated forest. It is perhaps, only the Cistercian terminology for forest, ‘desert’, that links these two places.

the wilderness of wirral

Wilderness – “In the wilderness of Wirral. Dwelt there but little that either God or man with good heart loved.” It has been suggested that the above was a reference to outlaws living in the wild country of Wirral. B.M.C. Hussain in his book, ‘Cheshire under the Norman Earls’, says that the people of Wirral and the citizens of Chester complained that they suffered at the hands of robbers lurking in the forest. However, the commons of the Wirral did not mention this but stated that it was because of the destruction wrought by game in the forest of Wirral, that the late Prince of Wales disafforested it.

The above ‘wilderness’ is probably a term used to describe the pre-disafforested “wild,” “savage,” “uncultivated“, “barren” desert-forest (silva/desertum). Wirral forest was a royal forest, a wild forest under forest law until 1376. According to the poet’s medieval imagination, such forests could be inhabited by mythical beasts such as, ‘wodwos’ wildmen of the woods, also bears, bulls, boars and wolves, a place therefore, where ‘Dwelt there but little that either God or man with good heart loved.’

It was likely thought, that perpetuating a traditional belief in such mythical beasts as ‘wodwos’, would help protect the royal forests from trespassers.

Today, traditional beliefs still help protect forests around the world, as follows: June 19th 2012 – Research by Ashley Massey, Oxford University, speaking at the annual meeting of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation in Bonito, Brazil, shows that cultural practices including beliefs in mythical beasts and animals that dance, have helped maintain forests in the West African country of the Gambia and Malaysian Borneo. Ashley Massey looked at the relationship between forest cover and the perceived existence of a dinosaur-like creature known as the “Ninki-nanka” in the Gambia and dancing animals known as “Kopizo” in the Malaysian state of Sabah. In both cases, locals believed that encountering mythological animals in the forest would result in death, leading them to avoid areas where they are believed to reside.

See: Traditional belief in mythical beasts help protect forests

There were outlaws hiding in most royal forests but Wirral was not officially disafforested due to its outlaw problem.

Wirral was an area under forest law, it belonged to the King until its disafforestation in 1376. Wirral forest had an outlaw problem, disafforestation would abolish the protection which outlaws and marauders derived from sheltering themselves in a royal forest, this would allow local law officers to enter into the area and apprehend criminals hiding there. However, the Black Prince’s disafforestation was because of the destruction wrought by game in the forest of Wirral and not by outlaws.

Description of document (click this link to download a digital copy of the original document)

Petitioners: Commons of the Wirral. Addressees: King.

Nature of request:

The commons of the Wirral state that, because of the destruction wrought by game in the forest of Wirral, the late Prince of Wales disafforested it, as can be seen from his charter made to them on this, and asked the King to confirm this; which he did. However, this disaforestement, charter and confirmation were made without process by ad quod damnum or in any other way, as the law demands. They ask that this disaforestement, charter and confirmation might be ratified by statute with the common assent of parliament, so that they will be not be annulled because they were not properly sued.

Nature of endorsement: [None]. Places mentioned: Wirral, Cheshire.

People mentioned: [Edward of Woodstock], Prince of Wales.

Date derivation:

Dated to 1376, as it is from the reign of Edward III but after the death of the Prince of Wales, and with reference to CPR 1374-7 p.378, which is dated 12 November 1376, and which mentions a charter of 20 July 1376, in which the King grants that the Wirral will be deforested forever.

Publication note: 1374-1377 p.378 (order to give William de Stanlegh, forester of Wirral, his profits and putures as before, notwithstanding the deforestation)

After 1376 Wirral was ordinary land and was already highly cultivated, Wirral could no longer be considered as ‘wilderness’, uncultivated land/forest. The Gawain poet can only be describing Wirral before 1376.