Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Identifying Gawain

and the Gawain Poet’s landscapes

For further information, click on the link buttons below:

To contact us by email click the button

a medieval mystery

Introduction

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a late 14th-century Middle English alliterative romance, describing an adventure of Sir Gawain, a Knight of the Round Table and nephew of King Arthur. The poem is considered a masterpiece of English Medieval literature. The priceless 14th century manuscript is now housed in the British Museum. The author of the poem is unknown and usually refererred to as the Gawain poet.

In the poem, Sir Gawain accepts a challenge from a mysterious ‘Green Knight’ who offers to allow anyone to strike him with his axe if the challenger will take a return blow in a year and a day.

<br><br>The Gawain poem as transcribed by J.R.R. Tolkien (The Lord of the Rings) and E.V. Gordon can be viewed here: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/cme/Gawain?rgn=main;view=fulltext <br>or click the button below to open in a new page.

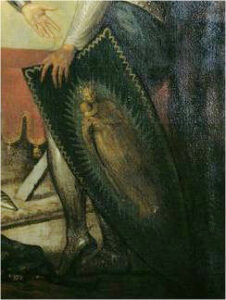

A poem for “the most famous of knights”, a great Huntsman, warrior and devotee of the Virgin Mary

The Gawain poem is unusual in that it mentions specific place names in England and Wales such as Wirral and Anglesey. Descriptions of landscapes are sometimes vivid, where the poet is obviously describing places he is familiar with. The poem is written in the 14th century Middle English dialect of an area where the borders of Cheshire, Staffordshire and Derbyshire meet. The central point of this location is known as ‘Three Shire Heads’, where once three boundary stones stood – see ‘The Gawain poet’s landscapes’.

There are also detailed descriptions of hunting, which suggests that the Gawain poet may have been a forester, a supervisor of the hunt.

Through historical references within the poem, alongside various book and online references, this website aims to identify the person to whom the medieval poem “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” was dedicated. The closing lines of the poem contain a very slightly shortened version of the Knights of the Garter motto, Honi soit qui mal y pense (Middle French: “shame upon him who thinks evil upon it”, or “evil to him who evil thinks”). These closing lines are the key to identifying our perfect knight.

Now þat here þe croun of þorne,

He bryng vus to his blysse! AMEN.

HONY SOYT QUI MAL PENCE.

'there was none more beloved and esteemed by the knights and ladies of his time.'

Piotr Sadowski suggests in ‘The Knight on his Quest Symbolic patterns of transition in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’, that the poem is concerned with birth, life and death, birth into manhood followed by a mature life filled with moral and psychological tests preceding an acceptance of death as part of the human game, as well as the acceptance of death itself.

Sir John Chandos, (died Jan. 1, 1370, Mortemer, France) – It is possible that the Gawain poem was written in memory of Sir John Chandos of Radbourne, Derbyshire, who died on New Years Day. A founding Knight of the Order of the Garter, Chandos was a great warrior, diplomat and Huntsman, a chivalric icon and Marian devotee ‘much loved by the King of England’ Edward III.

Chandos was considered a perfect knight as Gawain; a contemporary, Walsingham, says he was, ‘the most famous of knights’. Knighton says of Chandos that ‘he was the most talked about knight of his age’.

According to Froissart, the Barons and Knights of Poitou, regarded him as the ‘flower of all Chivalry!’

Sir John Chandos was mortally wounded on Dec 31 1369 during a skirmish at Lussac Bridge and died from his wounds on January 1st 1370, this mirroring Gawains anticipated death at the hands of the Green Knight, on New Years Day. An Arthurian poem ending on New Years day, being suitably dedicated to one of Edward III’s founding Garter Knights who, it appears, had the characteristics of a Gawain.

MEMORIALS OF THE MOST NOBLE ORDER OF THE GARTER, FROM ITS FOUNDATION TO THE PRESENT TIME. INCLUDING THE HISTORY OF THE ORDER; BY GEORGE FREDERICK BELTZ, K. H. LANCASTER HERALD.

Sir John Chandos – The splendid career of our hero closed on the morning of the 31st December 1369*. (Beltz goes on to give an account of Chandos’s career before he writes the following footnote concerning the knight’s death).

* Doubts have been suggested concerning the precise date of this event. According to Froissart, the attack upon Saint Savin was made in the night before New-year’s eve, —”la nuit devant la nuit de Van, au chef du mois de Janvier,”—the night, therefore, between the 30th and 31st December 1369. The skirmish near Lussac bridge, in which Chandos fell, happened on the following morning, and he died on 1st January 1369-70. Froissart and Beltz confirm that Chandos survived through the day and knight of the 31st December and died the following day, New Years Day.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight cannot be considered an elegy, although Gawain and King Arthur’s court believed that Gawain was going to his death on New Years Day. It is of course an adventure of a perfect knight, as Sir John Chandos was considered during the romantic revival of the 14th century. The Gawain poem is a story of how a true knight would confront death and accept his fate, especially if he were a chosen knight of King Edward III’s Order of the Garter.

John Chandos had interests in all the lands Gawain travelled through, including the three great forests of Cheshire. If travelling firstly through Wales, Chandos was Keeper of the park of Llwydcoed in south Wales and in north Wales, he was keeper of the forest of Estyn in Hopedale near Flint, close to the river Dee. Crossing the Dee into Logres/England, Chandos was Keeper and Surveyor of Wirral Forest in Cheshire. Travelling south east you would reach the park of Peckforton, at the base of Beeston castle, where Chandos was Keeper of the Park. Peckforton Park was an appurtenance of Delamere forest, of which he was also Keeper and Surveyor. Travelling east you would reach the Forest of Macclesfield, again Chandos was Keeper and Surveyor of this forest. As you leave Cheshire and enter Derbyshire, the county home of Sir John Chandos, you reach the Chase of Longdendale in the High Peak, where he was Keeper. He was also Chief Forester of the Forest of High Peak and constable of Peak castle, the administrative centre of the forest. All these positions, and more, (see Account of Master John Burnham the Younger, below for full list) Sir John Chandos held for life.

There is a very informative online book, The Perfect Knight, Sir John Chandos, by Stephen Cooper. This book tells the story of Sir John Chandos, the Derbyshire knight who served the Black Prince.

Advisor to the Earl of Chester, the Black Prince

Along with Sir James Audley, Sir John Chandos was the closest friend and advisor to the Earl of Chester, the Black Prince. He had advised and protected the Prince during the battles of Crecy and Poitiers. He was later to do the same for the Prince’s brother, John of Gaunt, at the battle of Najera.

Account of Master John de Burnham the Younger, Chamberlain of Chester, by Booth and Carr – Chandos was the prince’s devoted friend, and the most famous of his companions in arms. He visited Chester during the state visit of 1353 (and witnessed the charter granted to the community of the county, C53/162,m. 11), and again in 1354 (B.P.R.,iv. 136). His main connection with the county of Cheshire came through the newly-created, well-fee’d, but largely sinecure offices that he was given in the aftermath of the 1353 visit. He was appointed steward of the manor of Macclesfield. with Robert de Legh of Adlington, the elder, as his deputy, and also keeper and surveyor of the three forests of Cheshire (the letters for which do not survive, but see the grant of his expenses on 19 Sept. 1353 in B.P.R., iii. 122-23). As far as the forest office was concerned, it meant that the riding foresters of the three forests were regarded as his deputies.

He was granted the demesnes of Drakelow manor, plus £40 annual rent from Rudheath, in 1357 (ibid., 231, 267). On 13 September 1358, during the prince’s second visit to Cheshire, he was appointed steward of the lordship, and keeper of the chase of Longdendale, keeper of the forest of Estyn in Hopedale, and keeper of the parks of Peckforton (next to Beeston Castle) and Llwydcoed, all for life, with an annual fee of 100 marks and 2d. a day for the office in Longdendale (ibid., 314). As with the 1353 offices, he acted through deputies. Early in 1363, he granted £20 a year for life out of the issues of Drakelow to his esquire, Richard de Hampton, probably a Cheshire man (ibid., 473).

As mentioned, Sir John Chandos was given by the Earl of Chester, the position of Keeper and Surveyor of the forests of Wirral, Macclesfield and Delamere (refs. Booth & Carr and H. J. Hewitt, The Black Prince’s expedition). The chief royal official was the Keeper/Warden a supervisory forest officer. As he was often an eminent and preoccupied magnate, his powers were frequently exercised by a deputy. He supervised the foresters and under-foresters, who personally went about preserving the forest and game and apprehending offenders against the law.

Sir John Chandos also held high positions in France. He was made the viscount of Saint-Sauveur in the Cotentin and created the kings lieutenant of France and the vice chamberlain of the royal household, constable of Aquitaine and seneschal of Poitou. He became the constable of Guyenne in 1362.

Froissart poured praises on Sir John Chandos throughout his chronicles and of his death wrote:

“God have mercy on this soul! for never since a hundred years did there exist among the English one more courteous, nor fuller of every virtue and good quality than him”.

also

“He was so much beloved by the king of England and his court, that they would have believed what he should have said in preference to all others”.

If Froissart is to be believed, Chandos’s truthfulness must have been tested at some point. Was Gawain’s test a reference to this?

The man obviously demanded a great respect, from friend or foe, which was reflected at the time of his death. It was believed by many Frenchmen, that if he had survived, he would have been the only one who could have brokered a peace between England and France as he had the great respect of both sides.

Froissart’s descriptions of Sir John could be of a Sir Gawain or a Bertilak. Froissart describes how, when Chandos was appointed ‘regent and lieutenant of the King of England’ in 1361:-

‘[He] kept a noble and great establishment; and he had the means of doing it; for the King of England, who loved him much, wished it should be so. He was certainly worthy of it; for he was a sweet-tempered knight, courteous, benign, amiable, liberal, courageous, prudent and loyal in all affairs, and bore himself valiantly on every occasion: there was none more beloved and esteemed by the knights and ladies of his time.’

Gawain Poem: For I am well aware, indeed, you are Sir Gawain, whom all the world honours;

wherever you ride, your honour, your courtesy is graciously praised by lords, by ladies, by all who live.

Froissart’s physical description of Chandos

‘Among the knights, Sir John Chandos shewed his ability, valorously fighting with his battle-axe: he gave such desperate blows, that all avoided him; for he was of great stature and strength, well made in all his limbs.’

There are many links to Sir John in the Gawain poem, apart from his foresterships, that are hard to ignore as being mere coincidence.

Refs: The Household and military Retinue of Edward the Black Prince by Dr David Green -Account of Master John de Burnham the Younger, Chamberlain of Chester, by Booth and Carr – The Black Prince By Richard Barber, p.187 – Froissarts Chronicles

For further pages click the links at the top of the page, for next page click below: